First received 14 August 2025. Published online 15 November 2025.

DOI: 10.62478/GBAT7389

IPNS: k2k4r8k4u91kzjpj2cys3z5fu0hoevrg7758dtxvu61eonafnv09sr6h

Noel Packard, University of Auckland, New Zealand ([email protected], [email protected])

ABSTRACT: Why don’t we differentiate Internet history the way we demarcate other important historical epochs such as B.C. from A.D., pre-from post-WWII history, or the Dark Ages from the Enlightenment? This proposal advocates for differentiating Internet history into three epochs: 1) non-Internet (pre -1960), 2) Cold War/military networks (1960 -1995) and 3) commercial Internet history (1995 – onward). I argue that differentiating Internet history helps us recognize localized, historical and limited networked experiments in Cold War/military years, as representative samples of what life has become in a fully networked, totally digital world. Some literature review helps contextualize these arguments. After that Max Weber’s concept of a social honour sector of society, as interpreted by the author, is introduced to identify in a macro way the workforce that produced the commercial Internet and how it hinders us from differentiating this history. Then there is discussion about how differentiating Internet history can benefit those who pay for the Internet. Next, the analysis is demonstrated by comparing wealth inequality in Internet-differentiated case studies. Comparing how social science changes when we differentiate non-Internet from Cold War/military history from commercial Internet history helps: reduce blurring commercial-Internet with non-Internet history; invigorate comparative historical analysis and social justice analysis regarding Internet history, and; helps those who pay for the Internet understand Internet history better. An illustration of a demarcated timeline that differentiates non-Internet from Cold War/military and commercial Internet history is included, along with conclusions and questions.

KEY WORDS: Internet history, Internet histories, military networks, ARPANET, Cold War, Weber

1. Introduction

This is a proposal to differentiate Internet history into three epochs: (1) non-networked history up to 1960 when the Advanced Research Projects Agency Networks (ARPANET) and the funding to build ARPANET were approved by Department of Defense Directive (DoDD 5129.33); (2) Cold War/military network years, from 1960 to 1995 (when military networks were unavailable to most civilians), and; (3) commercial Internet years, from 1995 to the present. The Internet changed how we communicate transact business, work, play and shop. It could be “the costliest invention in the world” particularly since there is no single record, receipt or study, that shows how many billions or trillions of U.S. tax dollars were spent on “technical collection” R&D by taxpayers, and private investment (Packard 2023 a, pp. 7-8; Marchetti & Marks, 1980, p. 82). Today the Internet is a monopoly lifeline for transmitting business, communications and our collective and personal memory. Since social scientists investigate, differentiate and name epochs, why don’t we, and how can we, as social scientists begin to differentiate non-Internet from Cold War/military network and commercial Internet history the way we demarcate other important historical epochs such as B.C. from A.D., pre-from post-World War II history, or the Dark Ages from the Enlightenment, the Iron Age from the Stone Age and so forth?

Differentiating how society functioned either without or with the military or commercial networks helps clarify and improve social science. For example, comparing the global commercial-Internet era Covid pandemic to non-Internet era pandemics like the Black Plague means reflecting on how governments around the world thanks to the Internet – reacted in coordinated ways to fight Covid and relied greatly on expectations that civilians followed the authority of government often via the Internet—whilst the response to the Black Plague of the non-Internet years did not. The pandemic increased profits exponentially for global commercial Internet-dependent GAFA (Google, Apple, Facebook, Amazon) companies that never existed during the Black Plague. There may be more debate about differentiating a world before and after “Corona” history than there is about differentiating Cold War military network from commercial Internet history (Friedman, 2020 Park & Chung, 2020).

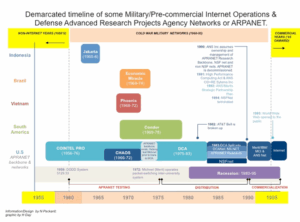

Figure 1: Differentiated Non, Cold War/Military and Commercial Internet Timeline

Figure 1 illustrates a timeline that divides history into non-internet years (pre-1960), Cold War/military-network years (1960-1995), and commercial Internet years (1995- onwards), as indicated by arrows at the top of the infographic. Testing, distribution, and commercialization phases of the Cold War military networks that became the global commercial Internet are demarcated in the timeline between the non-Internet and Cold War/military-network years (between 1960 and 1995). Some experimental military networks that were in operation during the Cold War are included in the timeline and noted by country on the left side of the graphic. These include Jakarta in Indonesia (1965-6), Phoenix Program in Vietnam (1968-1972), System Operation Bandeirantes (OBAN) in Brazil (1969-1974), Condortel (Condor) in Chile (1969-1978) and COINTELPRO and CHAOS in the US (1956-1972). These military intelligence networks helped transmit information upwards to command centers like the Pentagon and transmitted information horizontally to police and paramilitary forces to help facilitate neutralizations of alleged and real Communists and then others. I contend that these limited test-case, military microwave and radio networked experiments in social and economic management showed in a small scale the potentialities of what might be achieved in a fully commercially networked world and offer valuable, documented, reference points for differentiating Internet history and better historical comparative social science.

Sometimes, social scientists compare today’s neoliberalism economy to the economy of the Gilded Age while bypassing discussion about how military test networks helped to generate Brazil’s “Economic Miracle” (1969-1973) and helped generate wealth inequality through “free market”, “neoliberal”, austerity programs in Chile (1973-1976) during the Pinochet regime (Archdiocese of São Paulo 1998, pg. 50; Klein, 2007; Letelier 1976). Social scientists might consider that during the Great U.S. Recession of the 1980s new interactive computers were replacing older stand-alone (non-interactive) managed computers in “integrated” firms that had used “forecasting” and other “corporate techniques” to help them “roll with the punch” and keep “effective control of their integrated operation by statistical means” to protect them and their customers from economic downturns (Chandler 1967, pp. 87-96). Did the new interactive computers of the 1960s use forecasting and other procedures for mitigating the effects of economic downturns, as the older New Deal era managed computers had done? Differentiating Internet history might help answer that question. New Interactive computers offered revolutionary advantages to the elite few who tested and used them in the 1960s when interactive computers were as ominous and unknown to the public then, as AI is in the hands of vulture capitalists is today.

In the Cold War/military years (1960-1995) revolutionary interactive computer enhanced networks in the hands of an exclusive military-industrial-intelligence-complex were powerful tools being used for purposes kept secret from the public and the U.S. Congress. For example, Congressional investigations by the Pike Committee into how the National Security Agency was independently “passing into the realm of economics, as well as political” were terminated by the Congress itself, at the same time that former secretary of the U.S. Department of Defense, Robert Strange McNamara was heading the World Bank (1968-81) and G.H.W. Bush was head of the C.I.A. (U.S. 1975-1976 b, pg. 2079). The Great Recession (1980-1995) arrived as McNamara was leaving the World Bank, as email revolutionized the way that manufacturing could be done abroad, as the Bell Telephone System and its rate averaging system was broken up, and 1970s “Government Publications” about investigations chronicling intelligence community “crimes” shamed, angered and degusted Americans (Donner 1981, pp. 528-532; Halperin, Berman, Borosage and Marwick, 1976).

During the Great Recession (1980-1995) the U.S. lost its post-World War II full employment (not yet regained) while the government touted that the new so-called superhighway Internet would revive the economy. Was the government’s optimism tempered with consideration for how Cold War military networks in the exclusive hands of the military-industrial-intelligence-elites might have contributed to causing the Great Recession, or Brazil’s so called Economic Miracle, or to engineering a neoliberal and austerity economy in Chile? Differentiating Internet history would help find approaches to answering such questions. The answers may indicate that the exponential concentration of wealth that Peter Phillips (2018, 2024) writes about today, began in the Cold War military network years (1960-1995), perhaps when older managed computers in firms were replaced with new interactive computers that no longer functioned in a planned way that protected the economy from depressions, as older stand-alone non-interactive managed computers had done.

I presuppose that the concept of a commercial Internet and its prerequisite foundational Cold War military networks were considered a reality starting in 1960 after Department of Defense Directive 5129.33 (DDD 1959) established the funding and an organization, namely the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency, to build a communication system (Advanced Research Projects Agency Networks or ARPANET) for the military-industrial-complex to use for their own purposes following a recommendation by the U.S. Strategic Bombing Survey to build a communication system to service the military on a “continuing basis” (U.S., 1945, pg. 17). The continuing communication system included interactive computers that communicated with other cloned interactive computers, long-distance phones, teletype machines, television, telegraphy, and data transmission internationally and nationally via satellite, microwave and cable optic fiber. For example, as early as 1965 public networks of “teletypewriter terminals” and computers were used in Minnesota grade schools – so private companies and governments were using far more advanced computer-enhanced communication systems in the 1960s and earlier (Rankin 2015). The military transmitted electronic communications via non-visible, extensive long-distance microwave networks, satellite links, government radio channels, buried cable and microwave. Networks like these serviced military, Cold War anti-Communist social management experiments like: Phoenix, as written about by Belcher (2019), Johnson (1984), Valentine (2000) and Rohde (2011, 2013); Jakarta, as reported by Bevins (2020), Oppenheimer, et al. (2012), and Simpson (2010); and Condor as written about by Dinges (2004); Fischer (2015); Hammond (2011); Klein (2007); McSherry (2005); Lessa (2022); Letelier (1976); Nadel and Wiener (1977); and COINTELPRO, and CHAOS as written about by Churchill and Vander Wall (2002); Donner (1961, 1971, 1981, 1990); Halperin et al (1976) Keller (1989); and Zwerling (2011) among others. These 1960s network experiments tested how limited, localized networked surveillance and policing systems helped financially exploit populations in countries like Brazil, Vietnam, Indonesia, Latin America, and the U.S.

When these tests were successful the networks grew into an ongoing electronic and economic warfare or “condition” that assures a “smooth flow of resources to the core” (Halper, 2015, pp. 78-79) or as Neve Gorden explains, “killing terrorists is not necessarily adverse to neoliberal economics objectives, and actually advances them” (Loewenstein, 2023, pg. 57). Who defines “terrorists”, “core” or “condition”? I maintain that differentiating Internet history contributes to answering the question because it helps us compare localized, historical, limited man-interactive machine networked experiments in social and economic management (Phoenix or Condor for example) to what life has become in our fully networked, totally digital and commercial Internet world. I contend that limited networked experiments test cases like Phoenix, OBAN or COINTELPRO offer research opportunities that can be further explored with help from differentiation as proposed here.

Literature about why we do or do not differentiate Internet history is rare compared to literature devoted to “Internet histories”. The literature review below discusses some of that discourse. Then I explain how I use Weber’s social honor realm to frame discussion about the vast workforce that built, tested, and privatized the military networks into the commercial Internet and why it hinders us from differentiating Internet history. Then the focus shifts to the benefits of differentiating Cold War military, from commercial-Internet history for those who pay for the Internet (with taxes, telecom service payments, and our information). Finally, the analysis is applied to a contemporary problem to demonstrate how differentiating non-Internet, from Cold War/military network and commercial Internet history improves and expands social science. To demonstrate this, I use the social fact of growing wealth inequality and compare it in three different contexts: a non-Internet (pre-1960s context), a Cold War/military network context (1960-1995), and a globally networked commercial-Internet (1995 – onwards) context. Conclusions and questions follow.

2. Literature Review

Michel Foucault’s revival of Jeremy Bentham’s ideas about the pan optician were published in Discipline and Punish the Birth of the Prison (1975) and became a primary reference and focal point for much debate about surveillance for social science scholars. The book was published in French in 1975, the year that the ARPANET was transferred into the Defense Communication Agency (DCA) marking its end as an experiment and so called general computer and the beginning of its mission service in operations research for the Pentagon as DCAnet. From 1975 to 1996 the military intelligence communities used DCAnet for low-intensity warfare during the largest base building campaign in U.S. history when “stay-behind nets” or essentially portable computer nodes, were transplanted into bases worldwide arguably forming a foundation for the World Wide Web (Stein & Klare, 1973, p. 159). In 1996 when the World Wide Web (WWW) opened and people began to use the Internet (mostly in universities and companies since they had the best Internet access) Richard Evans (1996) the famed scholar of German, Third Reich and WWII history published Rituals of Retribution: Capital Punishment in Germany 1600-1987. At the end of his study about the German state’s use of corporal punishment Evans reflected on how his analysis of state governance and punishment compared to other approaches on these topics, such as Foucault’s approach.

Evans critiqued Foucault’s analysis in the mid-1990s when many students in universities were beginning to use computers, email and the WWW for the first time. Evans began his critique by praising Foucault’s popular Discipline and Punish because it helped him to formulate his own book. Then he turned to issues he had with Foucault’s approach, the first was that Foucault and his adherents “…treated the long early modern period as a single unity and failed to note that the ceremony of execution broke down at specific times and places and for specific exceptional reasons” (Evans, 1996, pp. 880-881). Evans found fault with Foucault’s overarching arguments that did not differentiate enough the exceptional times and reasons that caused historical changes.

Evans applied a differentiating analysis to Foucault’s book and life to show how Foucault’s arguments changed. Evans wrote that Foucault “discounted” the importance of “popular notions of justice” and the “multiple meanings of punishment” and failed to articulate the meanings of the Enlightenment (1996, p. 881). The Enlightenment led to ideas about the “rationality of the individual” as the “object and focus of judicial and penal practice” (1996, p. 881). As the world became disenchanted from popular beliefs and ceremonies it became enlightened to recognizing individual rights protected by laws, open trails, the right of the accused to a fair hearing, punishment commiserate with the crime and “equality of all citizens under the law” – achievements which Evans faults Foucault’s book for overlooking (1996, p. 881). I would like to point out that these overlooked areas of history are in keeping with a rather contemporary neoliberal orientation that discounts individual human rights and justice systems, and prefers corporate personhood rights and justice systems that are electronically (rather than human) mediated according to alleged or real “evidence based” information rather than jury by peers.

Evans critiques Foucault on different levels. Did Foucault really see historical theory or interpretation as a form of confining discourse? How did Foucault and Derrida differ in their arguments? What did other scholars think about Foucault’s approach of seeing “human affairs above all in terms of authority and obedience”? (Evans 1996, p, 883). How were these views shaped by Foucault’s “limit-experiences” or inspired by a “sado-Nietzsehean” view of history that colors Discipline and Punish (1996, p. 883)? Evans finds roots to Foucault’s approach “not so much in Nietzsche and de Sade as Marx and Mao” (p. 884). Evans writes about Discipline and Punish:

Published in 1975 the book emerged from and contributed to a specific historical and intellectual context, not just in France but also more generally. ‘Social control’ was one of the key concepts not only of much sociological work on deviance published in the early to mid-1970s but also of a good deal of historical research, social order was stabilized by the classification of the population as conformist or deviant, …Sociologists and historians taught that the ruling class under capitalism sustained itself by using the law as an instrument of class control, simultaneously indoctrinating the ruled into a belief that the combating of ‘crime’ was in their own best interests. This was the intellectual context into which Discipline and Punish fell (Evans 1996, p. 885).

Here I would like to point out that both Discipline and Punish and Rituals of Retribution fell into a context that saw the world anticipating the commercial Internet. From 1975 when Discipline and Punish was published to 1996 when the WWW made it possible for people around the world to fully utilize websites and Rituals of Retribution was published, marked the first decade when ARPANET turned DCAnet had expanded into a networked foundation for the WWW. Military and corporate interests that stood to benefit financially from a commercial Internet were already seeing computer terminals in universities across France and the U.S. (which shared network knowhow) fill up with students sharing their political views on one side of the screen, while military intelligence agents and telecommunications companies acting as third party private spies for government contracts, watched on the other side of the screen. Foucault’s career spanned the testing, and distribution phases of ARPANET. His career was peaking when the commercial Internet advanced revolutionary, evidence-free, invisible, electronic technical collection that the intelligence community “needed” (Aspray & Norberg, 1988, p. 37; Levine, 2018) after president Nixon was unseated in 1972 due to evidence of bugging in the Watergate scandal – which in turn ousted human spies from their jobs, so new computer “jockeys” could replace them (Moran 2017 p. 115; Packard 2023a, pp. 81, 94).

Many social scientists have made the same type of mistake that Evans faults Foucault for, by treating modern history as a “single unity” that fails to differentiate, discuss and demarcate how university networked tools provided convenient communication services to the universities first on one side of the screen, and provided the state with spy intelligence on the other side of the screen. As Shane Harris (2014) wrote in @war: The rise of the Military-Internet Complex “wireless communications were a spy’s dream” (p.14) and they also undermined the achievements of the Enlightenment in regards to individual rights and equality under law (a neoliberal dream). After President Nixon was unseated due to wiretap evidence, police forces in the U.S. and France and other countries transitioned to wireless and computer enhanced forms of evidence-free surveillance to help them suppress, among other things, student riots in the modus operandi of the FBI’s “Responsibilities Program” which protected spies’ privacy, while the subjects of police surveillance lost their privacy rights (since they had no evidence as to how the surveillance was done to use in court) (Packard, 2023, b, p. 33-32 fn. 13, 2023b p. 200, Rosenfeld, 2013, p. 35, Theoharis et.al., 1999).

Evan’s arguments along with Foucault’s, helped set the stage for a growing debate among surveillance and other scholars regarding whether or not the panopticon should continue to be the leading model for analyzing surveillance. Out of the debate came the book, Theorizing Surveillance; The panopticon and beyond edited by David Lyon, a leading scholar in surveillance studies and Director of the Surveillance Project at Queens University, Ontario, Canada. Early in the book’s Introduction Lyon (2006) wrote, “ I commence with a conundrum: the more stringent and rigorous the panoptic regime, the more it generates active resistance, whereas the more soft and subtle the panoptic strategies, the more it produces the desired docile bodies.” (p. 4). This sounds a lot like what Frank Donner (1981) who (in contrast to Foucault is perhaps the most overlooked surveillance scholar) wrote in The Age of Surveillance: the aims and methods of America’s political intelligence system. Donner wrote:

The impact of surveillance on the individual’s sense of freedom is enormous, and for this reason it yields the greatest return of repression for the smallest investment of power. Because it is so efficient, surveillance has transformed itself from a means into an end: an ongoing attack on nonconformity (Donner, 1981, pp. 6-7). In other words the more non-evident the surveillance the more (hidden) power potential there is to make people conform to the norms desired by the social realm spies and their market and party realm employers.

The first essay in Theorizing Surveillance was written by Kevin Haggerty and is entitled, “Tear down the walls: on demolishing the panopticon”. This is the essay where Haggerty (2006) makes the provocative statement, “Foucault continues to reign supreme in surveillance studies and it is perhaps time to cut off the head of the king” (p.27). It appears the debate over whether or not the panoptican should remain the model for surveillance studies had reached a boiling point of “active resistance” against the visible scholarly “king” and had generated the kind of debate that spies could enjoy from the other side of the screen (far more titillating than Donner’s hard boiled analysis). The frustration leading to this active resistance grew out a jungle of “secondary literature” that strives to make more meaning from Foucault’s works but ultimately serves (perhaps intentionally?) “as a vehicle for bewilderment.” (Haggerty 2006, pg. 36).

Haggerty goes on to discuss how surveillance is neither “good nor bad” it is something to be weighed and meaning made from. This is a very different approach to surveillance than what can be seen in Donner’s or Pyle’s Cold War era, American, on-the-ground observations of surveillance as a tool in the hands of military staffs with entrenched and biased national and job security ideologies and access to powerful and special computing tools (Donner, 1981; Pyle, 1970; 1974, p. 361). Perhaps it is unsurprising that French and U.S. scholars would avoid in-depth study about counterinsurgency surveillance that roots to the Vietnam War or the surveillance of U.S. 1960s anti-Vietnam War protestors since the U.S. and France have mutual interests in deflecting scrutiny about Vietnam War crimes? I discuss this in an interview (Group S 2015). Perhaps this has something to do with why French or U.S. professors, publishers and editors are in the position of kings overlooking surveillance discourse, rather than Vietnamese or Latin American scholars?

Haggerty asks, “what are we to make of the particularities of the agents conducting surveillance?” Foucault’s response is that it doesn’t matter and the theory doesn’t dwell on this. Haggerty writes that it “matters enormously” who is conducting the surveillance and launches into a discussion about this but fails to recognize that Foucault is, in a sense, telling us correctly that spies are not suppose to matter – they will be and do whatever is necessary to make you give up your thoughts, intentions and actions to them, because it is the target who really “matters” and not mattering is what protects the spy.

Four years after Theorizing Surveillance was published Gilbert Caluya (2010) wrote an article entitled, “The Post-panoptic society? Reassessing Foucault in surveillance studies”. Caluya reiterated the arguments of Haggerty’s article and advocated for returning the king to his throne over surveillance studies because a new book of Foucault’s 1970s lectures regarding security shed light on areas of relevance to the field of surveillance studies. Foucault’s new (2007) book about his old lectures, entitled, Security, Territory, Population focused on the history of “governmentality” from the first centuries of the Christian era through the modern state. The word “security” is certainly a loaded one in relation to U.S. intelligence during the 1970s as ARPANET became DCA net for OR national security mission service. And for Zionists in Israel security meant building up a surveillance state in Palestine and a surveillance/occupation industrial complex with U.S. support as Halper (2015) reported in War Against the People, Israel, The Palestinians and Global Pacification (p. 81-82). Foucault however, does not take the discourse about power, surveillance and occupation in that direction, instead he introduces a discourse about bio-power. During the 1980s and 90s Students world-wide focused on Foucault, decolonization, gender and identity politics while hard won, fact-laden, grounded literature about the abuse of military surveillance that went hand-in-hand with neoliberal policies, occurring in military networked countries, written by researchers like Donner, McClintock, Pyle and even U.S. government and military officials was ignored by the academy – in favor of discourse that lead to a bewildering array of secondary and fragmented literature. Why? The answer to that question could be investigated using differentiated Internet history methods.

Caluya ends his article by quoting from David Murakami Wood who argued “While it is sometimes acceptable to use the panopticon ‘as a badge of identity’ it is not ‘when the Panopticon, standing in for Discipline and Punish or for Foucault, is used as a straw man to be knocked down in order for the author(s) to set up their own approach’ (2007, p. 257). This is interesting because anyone who has some basic knowledge about spies knows how eager spies are to collect intelligence about any new approaches that scholars or any target may have. Whether the spy is human or a machine or usually a combination of both – that is the spy’s job – to give new information about a target’s approaches over to their employers and databank it for future reference. In a sense Foucault is both a straw man and a king who like a spy speaks in vast array of words and phrases that provokes people to give up their thoughts, feelings, tendencies, ideas, approaches – which can be recorded for future reference by the surveillance camera, the terminals in university computer labs, the hidden audio recorders in rooms or by the informant student who works part time for the intelligence community or the professor who is an informant to the government and so on. It seems like a missed opportunity that before turning to Foucault, surveillance studies scholars did not mine the rich literature of dozens of 1970s “Government Publications” about government investigations by the Church, Pike, Rockefeller, Ervin and other committees into intelligence community abuses (listed in Donner’s (1981) Bibliography) and accounts by Cold War era investigators such as Cook (1997), Halperin et. al (1976); Hitch and McKean (1965); Klare (1972); Klare and Arnson et. al. (1981); Klare and Kornbluh (1988); Keller (1989); Letelier (1976); McClintock (1985a b, 1992); Nadel and Wiener (1977); Norberg and O’Neill (1996); Pyle (1970, 1974); Simpson (1988, 1995); Stein and Klare (1973); Marchette and Marks (1980); Johnson (1984); Valentine (1990/2000) to name only a few sources who provide material to root more grounded theories of surveillance and its “role in …reinforcing social inequalities” in (Haggerty, 2006).

Universities have been intertwined with both making and testing networks; testing included spying on students and faculty in universities and sending the intelligence to military contractors (often university contracted staffs) for electronic word processing and software development as Donner (1971, 1981), Rosenfield (2013), Zwerling (2011) and Pyle (1970, 1974) wrote about and as many U.S. government military appropriations meetings and the Church Committee findings testified to (U.S.Congress. Senate. 1972; Packard 2020a). Universities like MIT or University of California, Stanford, Harvard and Michigan State contributed to developing and testing the hardware and software for the networks and in so doing they also developed “planning-programming-budgetting” that enabled the new computers to process the multi-year military contracts that would continue funding the R&D (Hitch, 1966, p. 36). Since it is impossible to give a really comprehensive or total account of Internet development history incremental Internet histories are written by authors such as Abbate (2001), Waldrop (2018), Kleinrock (2010), Shah and Kesan (2007), Leslie (1993), Levine (2018), Norberg and O’Neill (1996), Newman (2002), Waldrop (2018), Zuboff (2018) and many others.

Internet histories are recorded in physical and on-line books, journals, National Security Archive and corporate archive documents and even movies such as Werner Herzog’s (2016) Lo and Behold, Reveries of the Connected World which re-visits the computer at University of California, Los Angeles that first “talked” to another computer in early interactive computing experiments. Within the vast array of surveillance and Internet histories there are histories tailored for certain kinds of readers, certain kinds of scholarship, certain age groups, or made more autobiographical or more technical. This was the subject of a Special Issue of Internet & Culture edited by Thomas Haigh, Andrew L. Russell and William H. Dutton (2015). Each of the articles in the Special issue presents part of a spectrum of Internet histories that like an ideal type Internet history publication, represents a lot of other Internet history literature that more-or-less assures readers (and taxpayers) that the Internet pioneers did their jobs and helped build a better networked society, with some challenges along the way. Since basic university research funding relied on the U.S. taxpayers it is important to assure readers that their taxes were spent on inventions that they can feel positive about – like email, pcs, wireless phones, lower phone rates, Google, Microsoft and the WWW. Would we expect mainstream Internet histories to recount “negative” Internet histories such as how FBI, CIA and police informants spied on law abiding civilians, students and faculty on U.S. university campuses and elsewhere during the years of COINTELPRO (and CHAOS, the first CIA program to officially run on domestic soil by request of the president) as reported by Churchill and Vander Wall (2002), Pyle (1970), Donner (1971, 1981), Rosenfeld (2013) the Church Committee reports and Zwerling (2011)? In 1973 a three year U.S. military investigation concluded that vast amounts of unconstitutionally and illegally spy collected “ raw data… was pumped through the system and dumped on potential users — unsorted, unchecked and unevaluated” (Packard 2023a, p. 208, fn. 84; U.S. Congress. Senate 1973, p. 49). This side of network history rarely appears in the literature. Perhaps the history of the Internet has a shadow history that we silently agree to ignore? Why?

Haigh, Russell and Dutton present an excellent summary of major actors in Internet history and the scholars who documented their achievements. The editors discuss why Internet histories are so diverse and three problems they see in the literature namely, (1) “Whig history”, “. histories that celebrate the present as the best possible outcome” (Haigh, Russell, Dutton 2015, p. 152), (2) teleological histories that “ignore the messiness of the past” and (3) Internet histories that tend to be too close to the sources. I see these problems in the literature too. The editors provided a spectrum of Internet histories that get around these problems fairly well, offering an interesting range of mainstream and not-too-controversial Internet history in keeping with what is expected in an academic environment that needs funding from the government. But why do Internet histories in the academy discount controversial Internet histories of the formative Cold War military network years? For example, the student protests against the “Octaputer” (military computers on university campuses) that cast interactive computers as a threat to democracy and freedom (Levine 2018, pp. 64-71) also gave the police more job opportunity to “vacuum” up spy data on the protesters (U.S. Congress. Senate 1973, p. 48) and to feed it into new expensive interactive military computers which once bought had to prove useful for something – such as helping to “..replenish the supply of subversives from the ranks of dissidents, to create a domestic climate more favorable to foreign policy changes in a cold war direction, and to discredit the predictable movements of protest against the threat of nuclear war, environmental damage and economic injustice” (Donner 1981, p. xv; Packard 2023 a, pp. 184-186).

I agree with Evans that differentiating history helps us examine how history changed at specific times. It also makes it easier to explore the Cold War military network era Internet histories sometimes excluded from mainstream genres of Internet histories. This section has shown that discussing Evans and Foucault and their debates requires a lot of detail that makes it difficult to see the larger socio-economic picture to contextualize the networks. How can we streamline this type of research so that it is easier to draw conclusions without research becoming focused only on individual actors, inventions, programs, debates and so on? The next section uses Alan Turing and his team of code breakers as an example of a Weber inspired “occupational status group” which offers a more macro way to talk about contributors to network development.

3. Weber’s three part society, the social honor realm and occupational status groups

Max Weber (1864-1920) is a famous German political-economist whose life and works warrant an introduction far too vast for this article. His works were imported into the U.S. during the interwar years by Talcott Parsons a Harvard sociologist. Parsons translated Weber’s (1995) The Protestant ethic and the spirit of capitalism in the midst of the Great Depression and it has never gone out of print. It is a case study of how religion shaped social life in a way that supported a capitalist economy. It set a tone for neoliberalism among leaders and austerity lifestyle for workers. It inspired people to work hard but also warned that with prosperity would come an “iron cage” of corporate machine enhanced bureaucracy (Weber, 1995, p. 181). Weber’s other works were translated by scholars in the U.S. and have gone global and are taught in a wide range of subjects from religion to law, economics and sociology. Leading Weber scholars like Sam Whimster and Keith Tribe have carried Weber’s works into the digital age.

Weber is best known for his ideas about rationality, his “Ideal type” concept, analysis about bureaucracy, charismatic leadership, politics and science, value neutral science and other aspects of modern, machine age political economics. In the Cold War years Max Weber’s translated works such as “Class, Status, Party” (1958, 180-195; 1978, 1: 305–307; 2, 932–939) first published in From Max Weber Essays in Sociology and later in Economy and Society helped foster a mindset for the U.S. academy and military-industrial complex. I use Weber’s three-part social model from “Classes, Status, Party” as a flexible methodology for talking about the Cold War military-industrial workforce in terms of groups or en masse. It also offers a way to talk about Weber’s political-economic theory regarding production, consumption, hindering the market and political decision-making.

My interpretation of Max Weber’s (1864-1920) social honor concept is drawn completely from my reading of “Class, Status, Party”. Today Weber’s ideas are used in many ways throughout the world, including his three-part model of society, which is interpreted by other scholars for their own approaches which I overlook. My Weber inspired methodology is explained in detail in my thesis (Packard 2023 a, pp. 20, 107-145) and how I arrived at my interpretation (decades ago) is discussed in the answers to the first two questions in a Sociology Group interview entitled, An Interview with Dr. Noel Packard: Survey of a Cluster of Pre-Internet Networks (Group 2025). The way I interpret Weber’s three-part social model has nothing to do with stratifying society in a hierarchy or triangulating the position of an individual, instead it allows one to “see” the social realm workforce en masse, who were testing, distributing and commercializing the networks according to legislative orders and keeping them and other special goods out of enemy hands and out of the commercial market – or hindering the market. Using Weber’s three-part model of society, his social realm concept and occupational status group ideas helps streamline analysis of Internet history, avoid having to individualize or particularize the history and find socio-economic history obscured by the fragmented histories.

Weber’s “Class, Status, Party” describes a society divided into the market realm, the party or power realm, and the social honor realm. The market realm is composed of workers and capitalists, who control the market, produce for the market, produce tax revenue and profits and reproduces’ itself. The party realm is the political leadership that makes decisions, gives orders, and monopolizes military force and tax revenue, corporal punishment and social change. The social honor realm is composed of “occupational status groups” (OSGs) who are skilled workers “on their honor” in service to party leaders, market capitalists and national security (Weber 1978 p. 937, 2:937; Packard 2023 a, pp. 111-132). The social honor realm controls lifestyle and consumes and conserves “special” goods, such as weapons, medicines, computers, networks, inventions, documents, state secrets, intelligence, etc., to keep them out of enemy hands and out of the Market realm (Weber 1978, p. 2: 937). Weber’s concept of OSGs helps me identify the obscured intelligence workforce that helped build, test, distribute, and commercialize the networks into the Internet. OSGs have more control over their work lives than wage earners in the Market Realm because they need to appear socially honorable even if conducting dishonorable acts in service to national security as ex-CIA agent Marchetti wrote about in his novel The Rope Dancer about a 1970s CIA spy. Political party leaders often trust OSGs with large budgets and little oversight. For example, the first Information Processing Techniques Office (IPTO) Director J.C.R, Licklider (Lick), had a yearly budget of $14 million to “support computer labs around the country, often with thirty to forty times the budget to which they had previously been accustomed” (Newman, 2002, p. 49).

Social honor OSGs such as intelligence, special agents, paramilitary, advisors, operation researchers, double agents and police have more freedom than Market realm workers or Party realm leaders to undertake dangerous or clandestine tasks in service to the Party or national security. The skilled occupation of code-breaking was a good environment to foster networked telecommunications in, since sensitive military intelligence had to be kept non-evident and transferred as fast as possible to command for data-banking and future reference. Tyldrum’s academy award-winning movie The Imitation Game (Tyldum, 2014) presents an example of an OSG led by famed code breaker, mathematician and computer scientist Alan Turing. Turing, his team and the machine he built (named Christopher) cracked the infamous WWII German Enigma code to help Allied forces win WWII.

Cracking the code gave the team access to information about where the Germans planned to drop bombs, but raised a new concern – was it viable to warn allies (and even the relatives of the team members) that they were in the line of German fire? What would the Germans think if their targets changed course? Wouldn’t the Germans detect something and change the Enigma code? Turing’s achievement had to be kept secret so he advised the military to generate a disinformation campaign to convince the public that the war was winnable based on superior British and U.S. military maneuvers, rather than on code cracking, counter-intelligence and statistical studies that would tell Allied forces which attacks to stop and which to let happen. In this way the war would be won with the minimal number of actions, using the maximum number of actions that could be taken before the Germans became suspicious (imagine applying the same statistical tracking analysis to individual people using the Internet everyday!). This plan grew into a program code named “Ultra” which became the largest store of military intelligence in history, and was kept out of the hands of enemies and the market. Donner’s observation that the “ ..impact of surveillance …is enormous,… it yields the greatest return …for the smallest investment of power.” (1981, pp. 6-7) seems true when the narrative in the film states that the famous battles that won WWII would not have been possible without the intelligence supplied by Ultra and regardless of the hyperbole about nations, freedom, armies, patriotism and bloodshed the war was won because of the efforts of “a half-a-dozen cross word enthusiasts in a tiny village in Southern England” (Tyldum, 2014)

The British and U.S. governments along with the press sowed disinformation about how the war was won and since the wars continued after WWII so too did the disinformation campaigns. Shortly after the war Turing was arrested for being a homosexual (a crime in the U.K.). The penalty was to take hormones that caused self-castration. Turing died by eating an apple laced with cyanide (perhaps this inspired the idea of the Apple mac computer logo?). Turing did not live long enough to become a “leaker” about how “Christopher” had helped win the war. Turning’s death was a warning to other scientists to maintain a certain kind of lifestyle by maintaining disinformation and being a heterosexual least they too lose their social honour standing.

Turing’s life, secrets, and demise were a warning to countless scientists, technicians, students, and academics during the arms race against Russia and the rise of the military-industrial-complex. The message to this skilled workforce may not have been spoken but was feared – uphold disinformation or risk losing social standing and honor. This modus operandi is similar to the behavior of “social honor realm” actors described by Max Weber in “Classes, Status, Party” (Weber 1958; Weber, 1978, pp. 1: 305-307, 2: 932- 939).

Today the story of how WWII was won remains a mixture of fact and fiction, myth and mystery still recounted by the same type of academic, intelligence and military experts that the Turing team members worked for, but also maintained by all of us. This is an example of how inventors and people near them, like those who created interactive computer networks, are also PR managers about those machines. They created new tools and demonstrated how they could be used and interpreted, until orders from superiors changed the conditions. Imagine the Cold War era 1960s, 1970s continuous communication system made of wireless components and powerful interactive computers that communicated with each other over vast distances via invisible satellite, fiber optic cable, and microwaves. This revolutionary informational infrastructure transmitted without evidence, stored, processed, and hidden electronic communications and financial transactions. The informational infrastructure inventors, testers and users were distributed across universities, countries and private companies. It would be hard to describe such an invention in its entirety. Like the blind men who each touch an elephant and try to describe the animal, the inventors of the continuous communication system or networks can describe only parts of the informational infrastructure. Like Turing, the scientists who built the Advanced Research Project Agency networks “backbone” (ARPANET) and Michnet and untold numbers of other networks (the predecessors to the Internet) along with the RAND and intelligence community agents who programmed the computers, would not have told the public about all the ways they tested and used the Cold War military computer networks.

Military inventions are usually publicly promoted in the spirit of discovery, progress, national pride and security by members of what Weber termed the “social honor realm” who specialize in managing, consuming, conserving special goods like the military networks, keeping them out of enemy and market capitalists hands, until ordered otherwise. How that job was done is reflected in the plentiful “histories of the Internet” by scholars such as Janet Abbate (20000), Frank Donner (1981), Christopher Pyle (1970),Thomas Haigh, Andrew Russell, William Dutton (2015), Arthur Norberg and Judy E. O Neill (1996), Philip Mirowiski (2002), Shane Harris (2010, 2014), Charles Hitch (1966), Phillip Cantelon (1993), Anne Jacobson (2015, 2016, 2019) and Paul Edwards (1996) along with many others including countless U.S. government investigation reports.

Contemporary and extreme examples of how OSGs (such as gangsters, paramilitary youth forces, and the Taliban) control lifestyle and have freedom to live duo-lifestyles (being socially honorable while performing dishonorable deeds) in service to Party leadership and national security while consuming and conserving special goods, are shown in Joshua Oppenheimer’s “The Act of Killing” and in Ibrahim Nashat’s “Hollywoodgate”. Both films document the role OSGs played in transition periods (when the Party and Market realms are weak) following U.S. military operations in Indonesia and Afghanistan. Neshat’s documentation validates Weber’s argument that when the market and political realms weaken, members of the social honor realm grow stronger (Packard, 2023 a, b; Weber, 1978). Both films validate Weber’s economic theory that social honor realm actors conserve and consume special goods like estates, arms, computers, inventions, land, resources, medicines, money, airplanes, drugs, luxury goods, women, slaves, etc. (Weber, 1978 2:937). Having introduced this proposal to differentiate non-Internet (pre-1960), from Cold War/military (1960-1995), from commercial Internet history (1995 onwards) and a macro way to discuss the workforce that built, tested, and commercialized the special networks into the Internet, the following section considers what hinders us from differentiating this history and in particular, Cold War/military from commercial Internet history.

3.2 What hinders us from differentiating non-Internet, Cold War/military from commercial Internet history?

Hindering social differentiation of the non-Internet, from Cold War/military and commercial history, benefits OSG’s who helped build, test, distribute, and commercialize the networks into the Internet—how?

It benefits neoliberal OSGs when Internet history is obscure, ahistorical, and colored by neoliberal interests. That makes it difficult for academics and journalists to apply Marxian or critical comparative historical analysis to the history of military experiments that tested military networks, thereby green-lighting them for mission service with the Pentagon and later for commercialization into the Internet. “Neoliberalism” anti-Communism, and national security interests colored all aspects of Internet development and together deflected Marxian and critical historical-comparative analysis of Internet history (Packard, 2023a, pp. 39-43). Neoliberalism, anti-Communism, and plausible deniability protected the special Internet invention from being studied, copied, socialized, or taken over by perceived and real enemies of the state (Marxists, Socialists, Communists, unionists, political activists, students, terrorists, and so on) (Packard, 2023 a pp. 23-47, 2023 b). Cold War neoliberal OSGs assumed the networks would be commercialized, rather than socialized or government-regulated and they had interests in taxpayers and Congress being unaware of how much money was spent on military networks, lest funding for the world’s most expensive invention be spent on social rather than military needs. At the same time some professors like C. Wright Mills (1916-1962) warned of the dangers of a “permanent war economy” in The Causes of World War Three. Norbert Wiener (1894-1964) America’s premier mathematician, award winining MIT computer scientist, a life-long backpacker or tramper, and founder of the study of “Cybernetics” (man-machine relations) warned that cybernetics in the hands of the military and corporations would have dire consequences. Wiener (1950/1954) wrote about this in The Human Use of Human Beings: Cybernetics and Society after he refused U.S. military contracts to do more R&D. Both Mills and Wiener died of heart attacks two years apart during the COINTELPRO years (1969-1972) and their books were marginalized by the academy. In contrast Michael Klare (1972), an emeritus professor of peace and world security studies, who wrote War Without End: Planning for the Next Vietnams has lived to see a permanent war economy unfold over the decades.

Differentiating history about the Internet is also hindered because Cold War/military networks contributed to neutralizing (pacifying or killing) Communists, socialists, and others considered enemies of the state. Neutralizing people who opposed neoliberal austerity programs and war was a way for military governments to test two-part networked operations to increase austerity (or poverty) and corporate profits while decreasing dissent in countries like Guatemala, El Salvador, Chile, Brazil, Indonesia, and the U.S. Arguably some of those 1960s tests were small versions of what is happening in Gaza. Some authors who wrote about Cold War/military era history and its spy and computer network related abuses include: the Archdiocese of São Paulo (1998); Bevins (2020); Ben-Menashe (2015); Blum (1972); Churchill and Vander Wall (2002); L.C. Cook (1997); Dinges (2004); Halper (2015); Halperin et al. (1976); Keller (1989); Kesan and Shah (2001); Klare (1972); Klare and Arnson et al. (1981); Klare & Kornbluh (1988); Klein (2007); Lessa (2002); Letelier (1976); Levine (2018); Marchetti and Marks (1980); McClintock (1985 a, b; 1992); N. Packard (2020a,b,c, 2023a,b); V. Packard (1964); Pyle (1970); Rohde (2013, 2011) Rosenfeld (2013); Stein and Klare (1973); C. Simpson (1988, 1995); B. Simpson (2010); Valentine (2000); Nadel and Wiener (1977) and dozens of government investigations into intelligence community abuses as listed in Donner’s bibliography in The Age of Surveillance (1981, pp. 528-532).

Cold War era OSGs designed military networks to be non-evident: 1) to avoid protests and enemy take-overs or attacks on the special military networks, and 2) to be invisible to civilians, taxpayers, scientists, academics, and the U.S. Congress—who the military feared, might reduce funding or try to socialize the networks (Packard 2023 a, pp. 243). Unlike telephone wiretaps or human informants, new wireless electronic communications were invisible and left no evidence of their intangible transmissions, and were hidden in electronic databanks – an improvement over land-line telephone wiretapping, which was the institutionalized information gathering technique that was “second hand nature” to U.S. police, FBI, red squads, and cooperative telephone companies from the 1940’s to the 1970s, (U.S. 1975-1976 a, pp. 945-947). Examples of discourses that discuss the revolutionary transition from human informants and wiretaps to computer-enhanced forms of mobile monitoring appear in works by Pyle (1970), Donner (1981, 1990), in testimony by Michael Hershman former Chief Investigator of the National Wiretap Commission, and former police officer Zavala, (U.S. Senate, 1975-1976 a, pp. 940-947) and Deputy Assistant Secretary of Defense David Cooke who served under ARPA founder, Secretary of Defense, Neil McElroy and NBC correspondent Ford Rowan (U.S. Congress; Senate, 1975) and in Coppola’s (1974) movie The Conversation.

Differentiating Cold War/military and commercialized Internet history is hindered because it encourages questions about clandestine operations, presidential orders, national security, and plausible deniability. Military networks were used for transmitting communications for illegal, libelous, and clandestine activities, such as a National Security Directive to combat terrorism with a “license to kill” and “go anywhere, do anything” (Simpson, 1995, p. 371). Informational infrastructure transmitting electronic communications made it more convenient for military abuses to occur in two ways: 1) communications were “plausibly deniable” for national and job security, and 2) the government could publicly say, as David Cooke said, there was “no evidence” of files being transferred, to fend off possible lawsuits and bad press (or what Weber termed “hard bargaining”) (U.S. 1975, pp. 20-25; Weber, 1978, 2:937).

While we take digital communication for granted, in the Cold War years most electronic transmissions were used exclusively in the military-industrial-complex realm, often with security clearances. As Communications professor Christopher Simpson, author of Blowback (1988) and National Security directives of the Reagan and Bush Administrations and declassified history of the U.S. political and military policy, 1981-1991 (1995) points out in his monumental book, security directives often contained information “intended for publicity within elites’ national security circles yet secrecy from the public at large” (Simpson 1995, p. 7). Electronic transmissions that carried presidential orders enjoyed immunity and invisibility in the name of national security. Communications like these could be sent via military networks and interactive computers from Washington, D.C., to remote locations without leaving evidence.

Capitalist and military interests were/are benefited by networks built into civilian societies without democratic decision-making, voting, or public debate about the network construction, the use or ownership of networks, or the tax money spent on them (McChesney, 1996). Why aren’t these topics discussed more in university courses? In the 1960s networks affiliated with Condor, OBAN in Brazil, or Jakarta in Indonesia served police in gathering information to neutralize and disappear alleged and real political activists. By the 1970s, new software made information gathering faster, easier, more automated, cheaper, wireless (and therefore less evident than “bugs” on landline telephone lines), and less dependent on informants who might become whistle-blowers.

These technical developments unfolded while neoliberal economic policies in Indonesia where installed by economists trained at University of California, Berkeley and a decade later similar policy was installed in Chile by Chicago University economists.

In the 1970’s as a Transnational Institute and Institute for Policy Studies researcher, Michael Klare tried to investigate how many computers the U.S. supplied to Latin America for police forces in operations like CONDOR – defined as “the collection, exchange, and storage of intelligence data concerning leftists” (Klare & Arnson, 1981, pp. 78-79). Despite using a 1966 Freedom of Information Act request, the answer was denied because it might disrupt normal trade. Back in the U.S. American activists were spied on, arrested and monitored for life, as Churchhill and Vander Wall (2002), Rosenfeld (2013), Donner (1961, 1971, 1981, 1990), Zwerling et al. (2011) and the Church and other committees wrote about. Campus protests against the military “octoputer” were not taken seriously (Levin 2018, pp. 64-71) and faculty strikes over the militarization of university R&D energized more university militarization, as Leslie (1993) wrote about. Reporter Danny Casolaro and many other people died or were murdered trying to investigate the genealogy of William Hamilton’s revolutionary, new, Phung Hoang Information Management System (PHMIS) or so-called PROMIS software that made tracking, retrieving and searching data possible (Ben-Menashe, 2015, pp. 127-144; Linsalata, 1991; Packard 2023 a, p. 86-87, 2023 b, p. 21). The Reagan administration gifted such software to governments, sowing expectations worldwide for a commercial Internet on which the software versions could be utilized (Packard, 2023 a, pp. 86-87).

Throughout the Cold War years Americans were subjected to clandestine wiretapping, spying, and harassment by police that grew out of earlier anti-Communist vigilante, private company protection services, Ford Motor Company employee relations and police “red squad” practices (Brison 2004; Churchill and Vander Wall 2002; Donner 1961, 1981, 1990; Keller 1989; Packard 2023 b, Appendix). The Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) professionalized these actions through the “Responsibilities” program, which was supposed to protect Americans from subversives who were considered “Un-American”, as Donner (1961), Rosenfeld (2013, p. 35) and Theoharis et al. (1999 pp. 30, 369) wrote about. The Responsibilities program ran from 1951 to 1955 and targeted civil servants for public smearing and job loss. This anti-subversive campaign secretly collected evidence that the alleged or real subversive could not see, have access to, or know how the evidence was obtained or stolen. The FBI shared ill-gotten intelligence with Party realm leaders like state Governors. These habits or patterns transferred into the learning and purpose seeking interactive military networks and then the commercial Internet. Today, people do not know who is spying on them, nor can we confront the spies, nor have access to what information spies and/or corporations use (or steal) to target us for abuses or the exploitation that Shoshana Zuboff (2019) writes about in The Age of Surveillance Capitalism.

Thousands of Americans and other people fell victim to intelligence programs like COINTELPRO, CHAOS, and others that followed after the Responsibility program. The targets of the Responsibilities programs suffered job loss, injury, blacklisting, and “exposure” by the Dies, Fish, or McCarthy commission hearings or even death (Brinson 2004; Churchill and Vander Hall 2002: Donner 1961, 1981, 1990; Halpern et. al. 1976). They did not know who spied on them, which benefited the FBI, the police, and political leaders, working together with impunity. Hoover’s Responsibility program modeled a pre-commercial Internet human system for forthcoming types of continuous, electronic, automated, counterinsurgency spy operations designed to purge alleged and real Communists and then others—without evidence of how the spying was/is done, without the victims being able to see the evidence used against them, know how it was collected, and without recourse to legal protection. Spying became automated and invisible, which protected the government as it proclaimed that there was “no evidence” of spying (Packard 2023 a, b; U.S. 1975 pp. 20-25). The 1974 movie The Conversation showed the public that spying was moving away from human-run spying and phone tapping to more automated invisible, undetectable, machine-enabled surveillance or technical collection.

Differentiating non-Internet and Cold War/military network from commercial Internet history invites scholars to scrutinize history in ways that may threaten OSGs social honor. Studying Cold War/military network history and differentiating Internet history is in the interest of social justice and invites further research. This section discussed why identifying and differentiating Cold War/military networks from Commercial Internet history is hindered. Now we’ll turn to why naming and differentiating Cold War/military from commercial-Internet history is beneficial.

3.3 Why is differentiating Cold War/military from commercial Internet history beneficial to those who pay for the Internet (with taxes, telecom payments, and information)?

Informed and accurate social science improves critical analysis, raises consciousness, and strengthens social justice. Social justice benefits from differentiating Cold War/military network from commercial Internet history because new social science is unearthed. Military/pre-commercial networked operations like Phoenix and Condor or Brazil’s “Economic Miracle” provide compact and more stationary examples of networked societies, which today’s changing society can be compared to. Likewise, comparing today’s fully digital society to a non-networked society fosters robust social science. For example, one might compare 1) the non-Internet, 1930s, Great Depression and its recovery to 2) wealth inequality generated in the aftermath of the Condor operation in Chile during the Cold War/military network years of the 1970s, to 3) today’s record-breaking global wealth inequality in a fully commercial Internet world. In the next section, I sketch this comparison to demonstrate how social science changes when we differentiate non-Internet from Cold War/military Internet from the commercial Internet history.

In contrast, comparing case studies about ever-changing commercial Internet conditions against other recent and changing commercial Internet case studies generates less meaningful conclusions or comparisons because the data is constantly changing and growing – particularly in a BIG DATA and AI context. Limited Cold War/military networked experiments like Phoenix or Condor are historical reference points against which we can compare the changing conditions of today’s entirely networked world. For example, if one wants to research targeted-killing in Israel or elsewhere today — then compare that case to an historical Cold War/military case. For example, comparing targeted killing today, to Phoenix program or Condortell system kills draws more meaningful conclusions than comparing ongoing, current, open-ended cases of targeted killings in, say, Palestine and the U.S. (where mass killings happen regularly, and police commit murder publicly) because conditions change before meaningful conclusions can be made. Likewise, historical eras that lacked electronic and interactive computer networks can be compared to today’s fully networked world to preserve information about how people lived without the Internet for thousands of years. Such social science could become a special good that might help save lives if the Internet becomes unavailable.

4. Testing the analysis to compare growing wealth inequality

The following sections demonstrate how I apply differentiated, non-Internet, Cold War/military, and commercial Internet history to a contemporary social problem to improve social science and opens avenues for social justice discourse. I follow the growth of networked society in the U.S. from the Great Depression in the non-Internet years to the Cold War/military network of Condortell, to today’s growing global wealth inequality in a fully networked post-Internet world. I pre-suppose a relationship exists between networked societies and increasing wealth inequality because networked society and wealth inequality have increased together. Inequality reports from the World Inequality Lab (Chancel, Piketty, Saez, Zucman, 2022), The Center for Budget and Policy Priorities (Stone, Trisi Sherman and Beltrán, 2020) and Oxfam (Riddell, Ahmed, Maitland and Taneja et.al, 2024) and Peter Phillips Giants and Titans books (2018, 2024) validate that wealth inequality grew after the advent of the commercial Internet in the 1990s.

4.1 The 1930s Great Depression in non-Internet America and Economic Recovery up to the Cold War/military network years of the 1980s.

The Great Depression (1929-1939) was an economic downturn that began before the New York Stock Market Crash of 1929. Gross national product (GNP) fell nearly 15% worldwide. Businesses, farms, and entire communities were financially devastated. Countless people were left homeless and unemployed and the U.S. government could not count them. This prompted the government to, among other things, develop the Social Security Administration outfitted with IBM contracted computers that could count the population in an automated way that improved upon earlier German census methods that used tabulating machines, employee “Work Book Law” and card indexes (Packard 2018, p. 7). While most people experienced hardship during the Depression, some people thrived. Private companies like IBM or DuPont survived the Depression partly because they had “integrated firms” that used early IBM managed, stand-alone, rented or leased computers, and “forecasting” or other “techniques” that protected businesses and consumers from economic downturns (Chandler 1967, pp. 71-102; Packard 2023 a, p. 28). After the Depression, there was wealth inequality, but it was not as extreme as today in our highly networked, electronic world. For example, the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities published Policy Futures: A Guide to Statistics on Historical Trends in Income in 2020 and featured a figure entitled “Income Gains Widely Shared in Early Postwar Decades— But Not Since Then” (Stone et al., 2020). The figure shows real family income as rising after 1945, thanks partly to government regulation (i.e., taxing the rich, mandating cost of living increases for workers, subsidizing housing, New Deal programs, etc.). In the 1980s household income began splitting up, with only the top 95th percentile of families continuing to enjoy rising income while other families began losing income and the split has grown ever since.

During the Depression, the U.S. government leased computers from International Business Machines (IBM) (the wealthiest company in the world at the time) for the Census Bureau, and worked with private companies and government agencies to help count the unemployed (Packard 2018, p. 3). This initiated a bureaucracy-building process that saw the emergence of the Social Security Administration, which had administrative branches and computers managed by IBM. New Deal programs and government investment in domestic programs to improve housing, schools, the arts, and youth work programs along with the growth of the new military-industrial-complex helped bring the American workforce into a full employment economy. The U.S. workforce benefited from a growing information handling, “white collar,” and middle-class workforce (Mills, 2002). Their taxes funded the rise of the military-industrial complex, including building the military informational infrastructure that became foundational to the Internet.

After WWII, the 1945 U.S. Strategic Bombing Survey recommended that machinery communicating intelligence “for coordination between military and other governmental and private organizations” be built on a “continuing basis” (U.S. 1945, p. 17). In 1959, Department of Defense Directive, No. 5129.33 ordered such a communication system to be built, authorized the funding and the Advanced Research Projects Agency to build it (DOD, 1959). With the advent of the Advanced Research Projects Agency, the DoD order, funding and a facility to build it, the ARPANET backbone became operational.

During WWII neoliberal economist Milton Friedman helped change U.S. tax laws to assure tax revenue “from the source” (Friedman & Friedman 1998, pp. 120-124) was available for funding the war effort. The language “from the source” is a typical neoliberal distortion of the concept of where wealth comes from. For the neoliberals wealth comes from the employers who set aside the tax monies that employees (the real source of wealth) earn – and that tax money is used for “planning-programming-budgetting” for multi-year military contracts (Hitch, 1966). In 1959 when ARPANET development was approved sociologist C. Wright Mills (1959) warned about the dangers of and endless war economy in his book The Causes of World War Three. The next year Hitch and McKean (1960/1965) wrote The economics of defense in the nuclear age (dubbed the “Pentagon’s Bible”) which introduced a rationale for why tax monies, available in advance, were a calculable source of revenue for endless multi-year defense contracts for future wars (and arguably for the largest budget recipient, Israel) (Packard 2025, p. 74). In 1962 Mills died of a heart attack and by 1966 the endless war economy he warned about was already in motion as Hitch described how multi-year military contracts received U.S. tax revenue, writing, “Considering the vast quantities of data involved in the planning-programming-budgeting system the only practical solution was to transfer the online operation to a computer system. This we have now accomplished” (p. 34).

From the 1940s to the 1970s government regulation of corporations and funding for social needs helped keep America’s wealth distributed across the population in a more equitable way. The Great Recession arrived after former secretary of the U.S. Department of Defense Robert McNamara left the World Bank (1968-81) and the Reagan administration entered the White House. In response to the mysterious “stagflation” of the Recession the administration implemented neoliberal policies that freed Americans from government regulations, like cost-of-living increases, taxation of the rich, protective labor, consumer, union and privacy laws, social and educational programs, and the rate averaged Bell Telephone system payment scheme that kept telephone rates affordable for low income families. The Great Recession gave the administration a reason to order the ARPANET backbone (original networks) be commercialized to stimulate the economy.

By this time the ARPANET backbone had been transferred into DCAnet (in 1976), and split, at the least, into ARPANET Research net, Mil net (Military networks) and Defense Research Internet (DRI). Officially the ARPANET backbone was decommissioned (if only on paper) and the National Science Foundation (NSF) oversaw the commercialization of the various networks into the commercial Internet. Internet management inverted to a commercial partnership of IBM, Michigan Educational Research Information Triad, Inc. (Merit), and Microwave Corporation, Inc. (MCI) (Packard 2023 a, pp. 214-250; 2023b, pp. 24-29). A fully employed workforce was unnecessary once the government no longer needed to fund the network R&D. Private U.S. industries could seek cheaper labor abroad since they could send work orders via the revolution of email. As the split between more affluent and low-income families widened, leaders anticipated that the so-called Internet super highway would revive the economy. Susan Strange (1996) captured the charater of this optimistic time in her book, The Retreat of the State: The Diffusion of Power in the World when burgeoning “telecom” companies entered the world market, staffed to a fair extent by members of the social honor realm and intelligence community, as Shorrock (2008) wrote about in Spies for Hire.

4. 2 Condor, Jakarta and Free Market Economics in Cold War/military Chile and Indonesia

After the government authorized building a continuous communication system in the form of the ARPANET (in 1959) and before the ARPANET backbone was put into service with the Pentagon (in 1976), the networks affiliated with ARPANET had to be tested since they were paid for with U.S. taxes. According to DARPA Director Dr. Lukasik’s 1972 testimony at the Subcommittee of the Committee on Appropriations for the Defense Department for Fiscal Year 1973, ARPANET would have had to pass “feasibility demonstrations, undertaken prior to the assignment of a mission to a specific military service,” (DOD 1972, p. 729; Packard, 2020 a, p. 38). I contend that some feasibility demonstrations were conducted in operations abroad, such as Jakarta in Indonesia, Phoenix in South Vietnam and Condor in South America, among others. The Condor system helped create wealth inequality in Chile following the 1973 U.S.-backed coup and the siege of operation Condor documented in Patrice McSherry’s (2005) book Predatory State: Operation Condor and Covert War in Latin America. Here is a mini-case study of a Cold War/military test case society, meaning a society in which networks benefited the social honor and party realms by helping to hinder or neutralize workers and middle classes of the market realm.

In 1973, General Pinochet waged a bloody coup against Allende’s newly elected democratic government and after that initiated the Condor system, a U.S.-assisted, man-machine, two-part operation that promoted neoliberal economic reforms while neutralizing dissent, as written about by Dinges (2004); Fischer (2015); Hammond (2011); Lessa (2022); Latelier (1976); McSherry (2005) among others. The results of this brutal operation was a reinstatement of inequality that advantaged capitalists and gave them more control over Chile’s government while impoverishing the middle classes and working poor. After Pinochet took power, he nurtured the “embryonic” Condor program, established as early as 1969, turning it into a full-fledged “system” for “transnational repression,” as Francesca Lessa (2022, p. 18) recounted in her book The Condor Trials: Transnational Repression and Human Rights in South America. Condor was part of an anti-Communist program to turn back the hard-won gains of Chile’s burgeoning middle classes who backed government land reforms and nationalized foreign companies. Like the Reagan administration, Pinochet’s administration attacked the gains of the middle classes. However, it went further by imprisoning, torturing, and disappearing likely untold thousands of people whom the government (with help from interactive computer networks) decided were political activists who had to be neutralized.

Condor’s two-part program of economic and military repression was reported on by Allende’s former ambassador to the U.S., economist Orlando Letelier (1976), in his article entitled, “The Chicago Boys’ in Chile: Economic ‘Freedom’s’ Awful Toll.'” Letelier described the contradictions of famed neoliberal economist Milton Friedman’s (1962) popular book about free market capitalism, Capitalism and Freedom. Letelier wrote that the “Chicago Boys” neoliberal reforms reduced Chile’s GNP, reversed Allende’s nationalized corporations, putting them back into the hands of multinational corporations, caused massive inflation and starvation, dismantled state regulation of the economy, allowed private speculation to skyrocket, and left unknown hundreds or thousands of tortured civilians disappe ared or in concentration camps. Letelier (1976) pointed out the irony of Friedman’s arguments for market freedom that repressed workers and middle classes, with a “system of institutionalized brutality, the drastic control and suppression of every form of meaningful dissent is discussed (and often condemned) as […] only indirectly linked […] to the classical unrestrained “free market” policies that have been enforced by the military junta.” (p. 137). Here I pause to demonstrate how differentiating this Cold War history allows us to make comparisons that connect the present to the past in meaningful ways that might otherwise be overlooked. Notice that elite OSGs saw the markets in Pinochet’s Chile as “free” while overlooking the reality that civilians of the market realm were brutally deprived of their freedoms and livelihoods in the interest of foreign capitalists. The same can be said for Israel today as it deprives Palestinians of their freedoms and resources, while overlooking the human rights abuses that it inflicts. Occupational status groups in Israel “battle tests” revolutionary technology-of-occupation subsidized by U.S. dollars, on the West Bank and Gaza, and profits from occupation-technology sales to other countries that follow Israel’s example – an example akin to what Pinochet (backed by the U.S.) imposed on Allende’s supporters in the 1970s (Lowenstein, 2023, p. 40).

In 1976 month after Letelier’s article was published, he and his U.S. assistant Ronnie Moffit were car-bombed in Washington, D.C. The press reported Letelier as a target of DINA (Chili’s secret police) transnational repression. Since the FBI did not intercept the attack in the nation’s capital the ARPANET had the opportunity to demonstrate feasibility by transferring information about the terrorist attack, perhaps as information “intended for publicity within elites’ national security circles yet secrecy from the public at large” (Simpson 1995, p. 7). The same year G.H.W. Bush was appointed head of the CIA, ARPANET was promoted to OR mission service with the Pentagon in the Defense Communication Agency (DCA) (renamed Defense Information Systems Agency (DISA) in 1991) and Milton Friedman was awarded the Nobel Prize for Economics based on his economic planning for Chile.